Bad Charity

Article published: Wednesday, April 1st 2009

Some readers of this blog may think I have it in for charities. I don’t – in fact, I work for one. I just think that charities, like family businesses, are a corporate form with an accountability gap (no shareholders, no paying customers, no electorate etc. etc.) which makes them perfect, in a few cases, as well-moneyed vehicles for social engineering, vanity politics, or worse.

Sometimes, though, charitable accountability itself goes mad. (Or to hell in a handcart. Whichever.)

One example is child sponsorship schemes, which have been balled out since the 1980s: not just for the expectation that sponsors should receive fawning letters of thanks from grateful children in the poor countries their grandparents probably pillaged; but for dividing communities into new haves and have-nots, generating conflict, and entrenching new inequality. I thought that most respectable development charities with child sponsorship schemes had abandoned the ‘pay the named child’ approach, in favour of a more equitable fiction in which the whole community benefits from projects funded by the aggregate money of notional ‘individual’ sponsorships.

Not in Suguta Marmar, a town in Samburu Central District in northern Kenya, where last week I met the staff of a (tactfully unnamed) international Christian charity, the major humanitarian NGO in Suguta. According to its local programme officer, the charity continues to devote most of its efforts to making direct payments to individual children.

I emailed the organisation’s Virginia offices, which told me that:

“[s]ponsorship sustains family-oriented programs such as: health care, day care, safe water, nutrition, education and training programs, and projects for handicapped children. Donations from sponsors are combined and used to benefit all of the girls and boys in the community, even those who may not yet have been assigned a sponsor. Children that have a sponsor may also receive gift donations from their sponsor, as well as correspondence through the mail. Each child and family that are enrolled or may not be enrolled in a particular project still receive the same services.

Special gifts are received by the child and/or family one hundred percent in hand and can be used for whatever they want or need, unless you advise certain instructions. We have guide lines on giving gifts so children and their families do not feel in the spotlight or left out as they receive or do not receive gifts.”

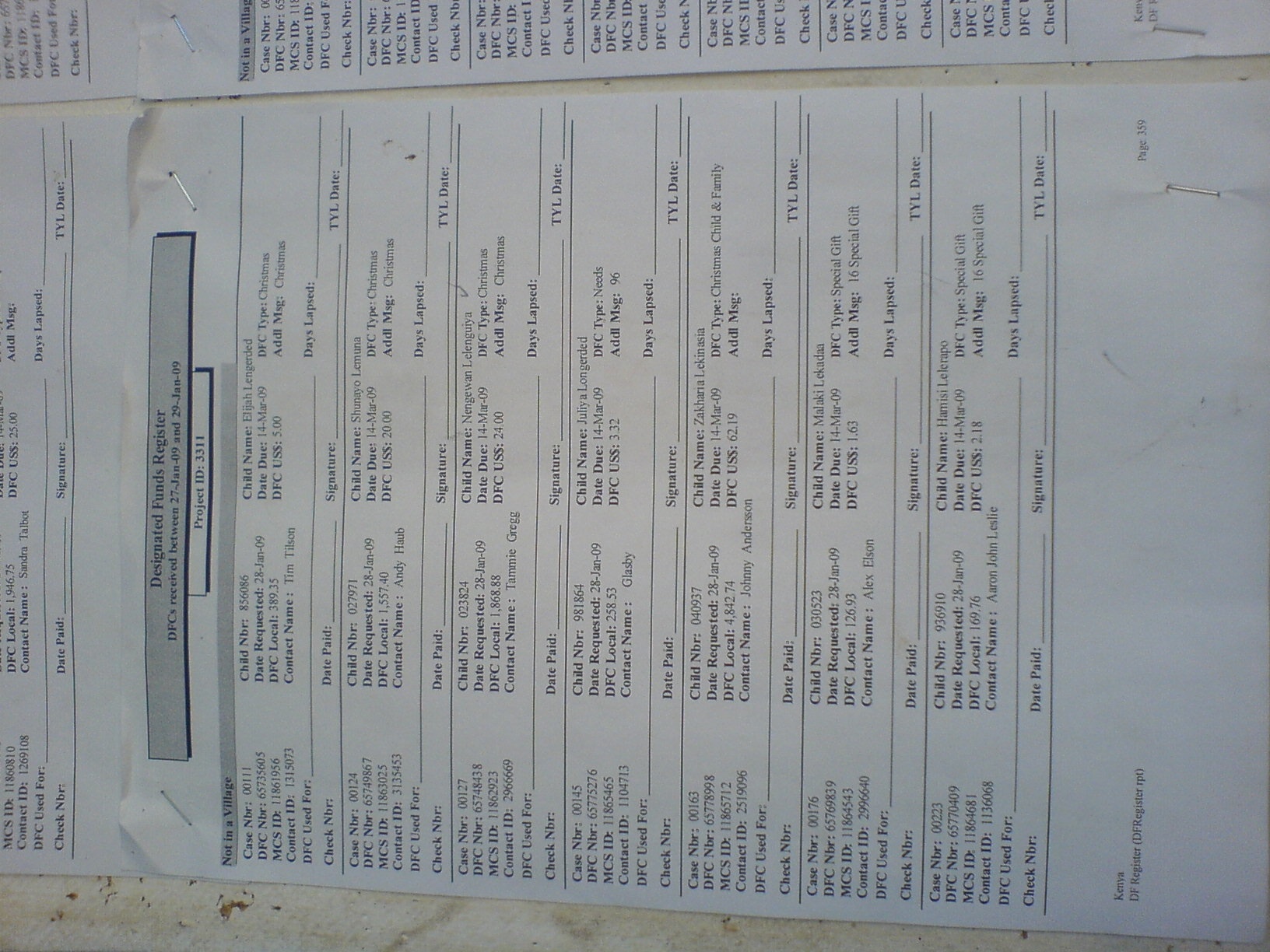

The “guidelines” evidently aren’t working very well. This list, pasted up on the charity’s Suguta office selected by a local committee, shows the extra Christmas ‘gift payments’ kindly sent by American sponsors in December. As you can see, benificent Johnny Andersson has decided that little Zacharia Lekinasia should get an extra $62.19 for a merry Christmas. This is quite a lot of money in Suguta Marmar: enough to buy two or three goats. On the other hand, Alex “Scrooge†Elson wants Malakai Lekada’s family to get just $1.63 (a ludicrous payment, just about enough to buy a bag of flour).*

(I wondered why the payments were such odd figures. Local staff just said that was how they came. Maybe it’s gift aid, or some other kind of tax rebate).

When I asked the organisation’s programme officer in Suguta what his organisation did there, he talked almost exclusively about cash payments to the families of individual children: both ‘special’ and regular payments. When I pressed him futher, he eventually told me that they did fund community-wide health interventions as well. But the individual sponsorship scheme’s accountability was one of its primary merits, he thought: individual sponsors knew exactly who was getting the money, and how much. He freely admitted that families were often extremely upset when they got less (or nothing) than their neighbours. I asked what happened if a child in Suguta gets sick but doesn’t have enough money from their sponsor that quarter for treatment? Or doesn’t have a sponsor at all? The rueful answer: if the treatment falls outside the routine primary medical care provided by the organisation – then tough.

There’s no doubting the sincerity of the organisation and its donors, or the real need in Suguta Marmar. And there’s perhaps recompense in the fact that the scheme has established a local committee which identifies needy families for sponsorship. But this community accountability opens up even more serious problems. Like local committees of all kinds in Kenya, it’s dominated by old, male community leaders (wazee), and open to political whim. Suguta Marmar, dominated by the Samburu community, lies on the faultline of a vicious local conflict between the Samburu and the Pokot, in which perhaps 40,000 people have been displaced since 2004. There are also Pokot residents in Suguta Marmar. But the programme officer told me, quite candidly, that recently the Samburu-run committee had started excluding Pokot children from the scheme.

So please don’t sponsor this child.

More: News

Comments

No comments found

The comments are closed.