Interview – David Dunnico

Article published: Sunday, September 19th 2010

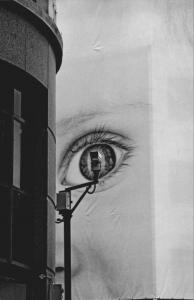

Tim Hunt spoke to David Dunnico, a documentary photographer from Manchester, who has recorded the rise of CCTV throughout Britain. His new book, Reality TV: CCTV Photographed by David Dunnico, is self-published through Blurb.com and can be downloaded for free at www.ddcc.tv.

Tim Hunt spoke to David Dunnico, a documentary photographer from Manchester, who has recorded the rise of CCTV throughout Britain. His new book, Reality TV: CCTV Photographed by David Dunnico, is self-published through Blurb.com and can be downloaded for free at www.ddcc.tv.

Tim Hunt: Tell us about your new book.

David Dunnico: I started photographing CCTV cameras a few years ago. I posted the photos to a flickr stream, “DDTV”. This helped me to make contacts and have discussions with other people interested in the subject. Photographs are always ambiguous [but] as I went on I realised there were specific things I wanted to say. The text [accompanying the images] grew out of extended captions.

TH: In many photos the cameras seem to have a character, or to communicate with each other. Do you feel they are taking on a life of their own; breeding in some way?

DD: The old style cameras have a character, like an alien dog’s head. You see which way they look; the lens is like an eye. Modern dome models are less visually appealing. I lined up groups of cameras to show how they’ve proliferated, point out the absurdity of one camera watching another and show how many different organisations are watching us.

They are procreating insomuch as people install them unquestioningly. I suppose we are witnessing a further retreat from civil society. People can’t pick up their homes and put them in a gated community, but they can install CCTV. A Swedish photographer friend visited and as he walked down our street he set off one security light after another. He said how thoughtful it was of people to have lights illuminating the path for visitors. Maybe B&Q will start selling electric garden fences.

TH: There are several cameras with Union Jack Flags in the background. Do you think nationalism as an ideology lends itself to surveillance?

DD: Adam Curtis put forward the thesis that politicians, being unable to create a better world, promise to protect us from nightmares. You could say it’s politicians we need protecting from. Nationalism is a response to fear, rather than making people feel more secure. CCTV makes us more worried. It’s in the interests of those in power for us to be worried. It’s interesting that people are scared of outsiders – but it’s us CCTV is watching. We’re all suspects now.

TH: CCTV is sold to us as public safety. Do you think they cut crime?

DD: If they did, you’d expect Britain, with the most cameras, to have the lowest crime rate. They sometimes move crime to areas where there’s no CCTV and a trawl of footage can sometimes get evidence after the event – but that’s not cutting crime, it’s helping police with their enquiries. In a few very specific cases CCTV can be effective [but] in the 1990s most of the Home Office’s crime prevention budget was spent on CCTV. Even supporters of CCTV have to ask if it was money well spent. I don’t go mugging people because I might get filmed, I don’t mug people because of the social values I have. A successful society isn’t based on fear and suspicion.

TH: Do the people in control rooms have any sense of a wider political project or do they see their work as public service?

DD: Very much as a service. In social housing schemes, the operators often live on the estates they film. Like most security work, it seems a fairly boring, low skilled, low paid, undervalued job. Some were very taken with the technology – like a big home entertainment system. One thing about remote observation is the observer views what’s happening as if it’s a video game. Individuals become [stereo]types.

People who run these systems know some are critical of CCTV. This was partly why I was let in: a way of showing they had nothing to hide. Just as they’d say “if you are obeying the law you have nothing to hide” from their cameras.

TH: “A sign of a broken society is the replacement of figures of natural authority and respect with enforcement officers whose role is often seen as being about revenue raising”. Would you say that Britain is broken and CCTV contributes towards this?

DD: A society based on making a few people ridiculously rich at the expense of everyone else has a broken heart. I don’t think CCTV is causing that. It adds to the background hum of paranoia: reminding people to be scared of those who won’t or can’t shop. At the moment, CCTV is largely considered a panacea, being seen to be doing something. Someone said to me, “I bet they put all the CCTV in rich places”. In fact, the big systems are usually in poor ones, keeping the peasants in line.

TH: “The driving force is the needs of the free market rather than a desire to restrict freedom”. But doesn’t the free market need to restrict freedom in order to exploit people? Might CCTV be part of a drive towards authoritarian capitalism?

DD: Capitalism has become the dominant force because of its complexity and subtlety. It’s hard to pin it down to a simple ideology; people believe it is the ‘natural’ order, even when they see it doesn’t work. However, at this stage, it needs people to be free enough to shop. You could say consumption has become the opiate of the people.

In ‘All Consuming’ Neal Lawson wrote: “We are told that this is a free country and that in a free country we will be happy. But we have simply the freedom to shop. A freedom that means everything is convenient but we still have no time for what we really care about, that makes us feel like kings as consumers but pawns as citizens…

… our pockets may be deep but our lives are shallow.”

Tim Hunt

This article features in the print edition of The Mule – Issue 10, out now for FREE around Greater Manchester

More: Features, Interviews

Comments

-

[…] not lucky enough to get a print copy of that esteemed organ, you can read the interview online by clicking here. Alas the book didn’t win Blurb’s Photobook prize, but you can judge for yourself […]

Pingback by Read on… « dunniphoto on September 22, 2010 at 7:51 am

The comments are closed.