Students hit out against youth work course cuts

Article published: Thursday, October 11th 2012

Outraged students have come out in protest against the University of Manchester’s plans to scrap its Applied Community and Youth Work Studies programme as part of an upcoming merger between two departments.

The University offers no similar courses where community and youth workers are not only taught the principles and practicalities of the job, but also directly contribute to young people’s lives by serving placements with local voluntary and charity bodies. Few other universities in the country offer a similar degree programme.

The University offers no similar courses where community and youth workers are not only taught the principles and practicalities of the job, but also directly contribute to young people’s lives by serving placements with local voluntary and charity bodies. Few other universities in the country offer a similar degree programme.

The course is also valued by students for its acceptance of people without A Levels, therefore widening university participation levels. A number of people who have received advice and support from those on placements through the programme have gone on to take the course themselves and help others in similar situations.

Current students were told at the start of term that they would be the last group to graduate with the qualification.

A university spokesperson justified the move by saying, “The Applied Community and Youth Work Studies programme has faced difficulties in maintaining its recruitment levels and… we do not believe that we will be able to recruit sufficient students in the future to make this programme sustainable.”

He added, “The current cohort of students will continue with their programme as planned and complete their degree as they expected.”

But a number of students disagreed, and made their opinions known at a noisy demonstration outside a University Senate meeting on Wednesday 3 October as the University’s highest decision-making body voted on whether the merger should get the green light.

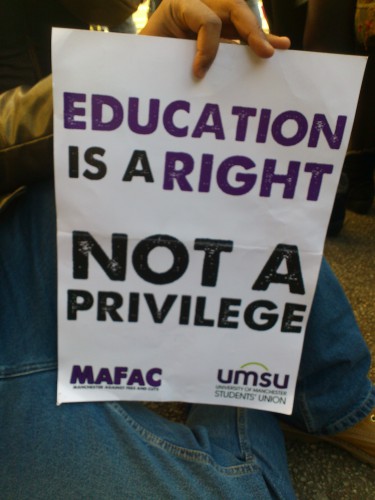

Roughly 60 current students and their supporters from the Students Union and Manchester Against Fees and Cuts held a carnival-themed protest outside the meeting, complete with sequined costumes, jugglers, face paints, a sound system. Students chanted “Save our Course”, while supporters distributed leaflets about the impact of the decision to both passers-by and Senate members.

In spite of the protest outside the merger between the School of Education and the School of Environment and Development that would end the community course was approved by a 24-12 vote, with around 10 abstentions recorded. No students from the course were allowed to attend the meeting, and attempts to raise the issue of the closure were ruled as being off-topic since the vote was formally about the merger rather than course cuts.

In spite of the protest outside the merger between the School of Education and the School of Environment and Development that would end the community course was approved by a 24-12 vote, with around 10 abstentions recorded. No students from the course were allowed to attend the meeting, and attempts to raise the issue of the closure were ruled as being off-topic since the vote was formally about the merger rather than course cuts.

Students who were present disputed the University’s explanation, and denounced the closure as a cost-cutting exercise.

One, named Jason, said that last year there had been more applicants than places available and that the course remained attractive, arguing that its closure would damage a number of local communities reliant on youth workers trained in Manchester. Although protesters knew that they themselves would be able to graduate, they said they were “protesting for a future generation with no voice.”

Two more protestors, Emily and Laura, said that despite claims by University representatives that not enough people on the course were gaining jobs after graduating, nearly all those who had graduated last year were now either employed or gaining further qualifications. This was especially important, they claimed, as “the course often accepted people without traditional educational backgrounds, meaning that it widened university participation.” They accused the University of acting without properly consulting its students on the matter.

Denise, who had been a youth worker for fifteen years before enrolling on the course, felt that the closure came as part of a wider abandonment of young people and by reducing the number of well-trained workers would compound problems caused by Manchester City Council’s closure of its in-house youth services. She pointed out that for much not in education, a youth worker that they could meet on the street was the only point of contact to discuss problems such as abuse or even sexual health.

Denise argued the University was potentially “recreating the problems of the past”, where a number of youth workers were undertrained or untrained, and remarked that she felt she had learnt more from two years on the course than fifteen years on the job.

Students and activists involved have pledged to organise further protests and to keep lobbying the Faculty of Humanities to retain the course.

Daniel Edmonds

More: Cuts, Education, Manchester, News

Comments

No comments found

The comments are closed.