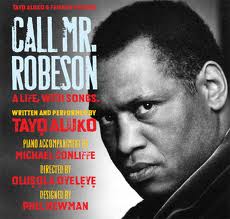

Theatre review: ‘Call Mr Robeson’

Article published: Tuesday, February 1st 2011

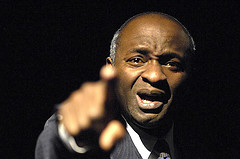

Tayo Aluko stars in a superb one-man show recounting the life and times of Paul Robeson: singer, actor, political activist and – in the eyes of the American authorities – communist troublemaker.

At one point in the 1940s Paul Robeson was regarded as America’s most popular singer. With the ability to fill theatre halls and command crowds of tens of thousands desperate to hear his soulful bass-baritone voice he appealed to both black and white audiences at a time when racial segregation divided the country and ‘coloured folk’ were considered sub-citizens.

In the eponymous role Tayo Aluko charts the life of this great man, explaining how a central figure in black American history could fade into such relative obscurity today. For the dazzling heights of Robeson’s international popularity and stardom would be equalled only by the extent of his eventual decline – a descent triggered in part by his steadfast refusal to abandon his principles and political beliefs. Aluko’s mastery of mannerism and ability to make it seem as if he is addressing you personally combines with an impressive musical score in a captivating feat of storytelling.

Son of a former escaped slave turned preacher, Robeson showed precocious talent in sports and academia but despite his intellectual talents would choose to pursue a career as an entertainer.

Having inherited a strong sense of social justice from his father it was on a visit to Britain in 1928 that he first became acquainted with ideas of socialism. This came through a chance encounter with a group of Welsh miners, a people with whom he would always feel a great affinity both on a human and musical level. At the end of a march from their home in South Wales to London in protest at their poverty and awful working conditions, their approach was heralded by beautiful and mournful singing. In their tones Robeson heard echoes of the melancholy spirituals that had been passed down by his own people from times of slavery.

It was at this moment that Robeson first recognised that the treatment of black people in America had its counterpart elsewhere in the world. This lead him to diagnose such oppression as a symptom of the class domination inherent within capitalism, or as he put it “the fight of my Negro people in America and the fight of oppressed workers everywhere was the same struggle”. Thus began Paul Robeson’s journey as a political militant, and he would go on to visit Welsh mining communities on numerous occasions as well as pledging his support for the International Bridge during the Spanish Civil War through a series of benefit concerts.

It was at this moment that Robeson first recognised that the treatment of black people in America had its counterpart elsewhere in the world. This lead him to diagnose such oppression as a symptom of the class domination inherent within capitalism, or as he put it “the fight of my Negro people in America and the fight of oppressed workers everywhere was the same struggle”. Thus began Paul Robeson’s journey as a political militant, and he would go on to visit Welsh mining communities on numerous occasions as well as pledging his support for the International Bridge during the Spanish Civil War through a series of benefit concerts.

The crystallisation of Robeson’s socialist convictions came on a visit to Soviet Russia, where he says “I was treated like a full human being for the first time in my life”. And the play reveals how his endless travels informed not only his political internationalism but also his appreciation of the shared musical heritage of all peoples: through his studies of traditional folk singing, be it in China, Wales, Russia or Africa, Robeson identified a recurring tonal theme of five notes – known in Western music as the pentatonic scale.

The script of the play is commendable in that it does not erase the unsavoury episodes of Robeson’s life, but portrays them with a pathos and humility that lends to an image of a real human being. Thus we see Robeson as a virtuous and admirable figure who nevertheless had his flaws which would ultimately lead to his downfall. On a political level, his almost blind support for communism reveals a streak of naivety which ran through many left-wing public figures and intellectuals of the time who, knowingly or not, turned a blind eye to the gross abuses of human rights under the Stalinist system in their support for ‘socialism’. And his increasingly vocal interventions and controversial political stance would eventually disenchant the public, as well as lead to his blacklisting from the country’s largest venues.

Perhaps Robeson’s finest hour – and indeed, the dramatic climax of the play – comes shortly after a failed suicide attempt which is conveyed brilliantly through an attack of cacophonous piano.

At the height of the anti-communist frenzy of early Cold War years, he is summoned before the House Un-American Activities Committee – a kind of de facto court which conducted public show trials in order to disgrace and blacklist suspected left-wing public figures. Responding to accusations of being unpatriotic, Robeson comports himself with an irrepressible passion and dignity, while his wit and oratorical finesse ensure that he emerges the moral victor. When asked why he does not simply emigrate to Russia, he replies: “Because my father was a slave and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here, and have a part of it just like you and no fascist minded people will drive me from it! Is that clear?”

For figures of popular culture today who rarely, if ever, pronounce themselves on matters of politics and principle beyond flaccid liberal entreaties, Paul Robeson’s belief that the artist “must elect to fight for freedom or slavery” is a timeless lesson.

Michael Pooler

Call Mr Robeson was on for one night only at The Lowry. For more dates of the tour across the country, visit: http://cmr.tayoalukoandfriends.com/

Comments

-

The 30’s had benefit gigs for the Spanish Civil War and all we have is Bono??

Comment by richard on February 1, 2011 at 1:39 pm

The comments are closed.