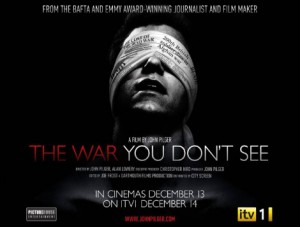

TV Documentary Review: ‘The War You Don’t See’

Article published: Tuesday, December 28th 2010

To what extent are the mainstream media and journalists complicit in the selling of imperial wars in the West? This is the subject of the latest documentary by journalist and filmmaker John Pilger. ‘The War You Don’t See’ was a welcome break from the usual ITV schedule of celebrities and cop shows, and provides a timely reminder of the role the media plays in regurgitating government propaganda in time of war.

The opening sequence comes from an American Apache Helicopter Gunship hovering above the streets of Baghdad, honing its sights in on a crowd of unarmed Iraqis. After some brief radio exchanges the signal is given: “Light ‘em up.” The ensuing massacre is harrowing viewing, as the sound of gunfire is interspersed with the calm voice saying, “keep firing.”

As is explained later this video was released by WikiLeaks in April 2010. The targets of that helicopter were a couple of Reuters cameramen, supposedly mistaken for ‘insurgents’, but the victims of this “collateral murder” – as it was dubbed by the former US soldier who leaked it – were dozens of civilians, mostly women and children.

The thrust of Pilger’s film is to ask just why stories like these so rarely make it into the mainstream. He starts the story with the father of PR and author of ‘Propaganda’, Edward Bernays, who once said, “The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organised habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society”. This remains as relevant as ever: for as long as you can effectively link symbols together – Saddam Hussein and 9/11 for instance – “the facts don’t matter anymore,” as one commentator puts it.

The toppling of the statue of Saddam: an act of imperial propaganda? Image from Gerard Van der Leun on flickr.

Pilger’s focus is mainly on contemporary conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan and Palestine, and how the now-ubiquitous government PR machines sell such devastating wars to domestic populations in the West. Fleshing out his unmasking of the real workings of the public relations industry are interviews and accounts from high-level international actors from government and global media.

The strategy of governments in ensuring that the ‘right story’ is reported is shown as consisting of a two-way relationship, which involves the consent of journalists in accepting official versions of facts in exchange for privileged ‘access’ to information and establishment figures.

“Journalists like to be part of the game, part of the inside crowd, and therefore conventional wisdom is the best wisdom,” says former CIA analyst Ray McGovern. The nature of this game is illuminated by Carne Ross, a senior British diplomat in the run-up to the Iraq war, who explains how they would “control access” to government. The extent of this stranglehold on the chain of the press collar is made clear in the frankness of his admission that “if journalists were not particularly supportive of our account we’d freeze them out.”

Another target of Pilger’s analysis is so-called ’embedded journalism’, the practice whereby reporters follow combat units often deep into site of conflict. These media actors are shown to be little more than government mouthpieces, as the military controls where they go and when, what they see – and in many cases what they are allowed to report. McGovern estimates 80-90 per cent of stories emanating from such sources are “officially inspired.”

But what of the government line that it is committed to spreading democracy around the world? In the words of British historian Mark Curtis, the proper reaction of journalists should be to burst out laughing. He places this in historical context: “There’s simply no history of that at all. Britain has always been on the side of authoritarian, repressive regimes – the Omanis, the Saudis, the Egyptians – these are our allies.”

Yet, as is shown, the selling of the government line and such myths to the public can only be achieved with the willing collusion of those reporting. Former BBC correspondent Rageh Omaar, the Observer’s David Rose and CBS anchor Dan Rather are three who express shame for what they now see as complicity in the invasion and occupation of Iraq. They readily admit how certain stories and facts were ignored when they “didn’t fit the script.”

‘The War You Don’t See’ shows the frightening extent to which the Iraq War was not some one-off event where normally reliable journalists were duped by Tony Blair and Alistair Campbell. Rather, the problems of biased media are systemic and permeate the very fabric of media culture.

‘The War You Don’t See’ shows the frightening extent to which the Iraq War was not some one-off event where normally reliable journalists were duped by Tony Blair and Alistair Campbell. Rather, the problems of biased media are systemic and permeate the very fabric of media culture.

Although doubtlessly important, the subject has been done to death a little over the past few years. For while critical media analysis seems to have a mild obsession with war reporting, this bias isn’t confined to government foreign policy and the Foreign Office isn’t the only institution which uses PR. Journalists aren’t only embedded in the military, but in the police, corporate bodies and practically every centre of power that dominates people’s lives. Where are the documentaries exploring these more mundane and everyday media biases?

Independent and investigative journalism which speaks truth to power can still make a difference, Pilger maintains, while projects like WikiLeaks are breaking new ground in the dissemination of raw information and facts for public examination. He dedicates the film to those courageous independent journalists – many of whom have lost their lives in these conflicts – who still work to uncover the brutal realities of modern-day war.

Pilger’s earnest manner comes across at times as sanctimonious and his attempt to pull on the heartstrings is unnecessary, as the material can speak for itself. For seasoned activists ‘The War You Don’t See’ will be covering a lot of old ground, but for others it’s well worth a watch.

Andrew Cox

‘The War You Don’t See’ aired on 14 December but is available here on the ITV Player until 14 January 2011.

Comments

No comments found

The comments are closed.