I heart corporate MCR

Article published: Friday, August 26th 2011

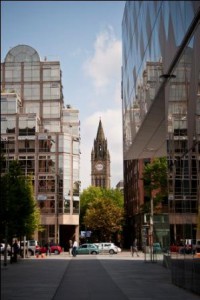

In the words of the city’s tourist board Marketing Manchester, today’s “I Love MCR” day will prove to the world how “the people of Manchester are proud of their city and united against anti-social behaviour”. But will this campaign unite our community, or paper over the social tensions driven by the dark side of the city’s regeneration?

There was an odd atmosphere the morning after the riots. Hundreds gathered in Piccadilly Gardens to assist the cleanup, and although their efforts were largely symbolic thanks to the hard effort of council cleaners who had worked through the night there was a genuine desire to get the city “back to how it was”. Some remembered past troubles; the IRA bomb, the EDL demo, drunken Rangers fans wrecking havoc in the main squares, and were confident the city would bounce back.

There was an odd atmosphere the morning after the riots. Hundreds gathered in Piccadilly Gardens to assist the cleanup, and although their efforts were largely symbolic thanks to the hard effort of council cleaners who had worked through the night there was a genuine desire to get the city “back to how it was”. Some remembered past troubles; the IRA bomb, the EDL demo, drunken Rangers fans wrecking havoc in the main squares, and were confident the city would bounce back.

Council leader Sir Richard Leese hailed the response as “a real demonstration of Manchester pride”, one which sent “a powerful message to the thugs that have trashed our city”. Yet tensions lurked underneath the “I Love MCR” face paint and strained cheer. At one point a man began to harangue the crowd, accusing those present of “taking people’s jobs and giving them to students”. To jeers, he was led away by police.

With admirable efficiency Marketing Manchester, the public relations agency subsidised over £1 million each year by Manchester City Council to attract tourists and big businesses to the city region, quickly capitalised on this civic sentiment. A major advertising campaign was launched to lure back shoppers to the city centre, the centrepiece of which is the “I Love MCR” day timed to coincide with Manchester Pride and the August bank holiday weekend.

Rebranding a riot

Few Mancunians will be unaware by now of the social media-savvy campaign. Celebrities such as Formula One racer Jenson Button have been drafted in, contentious plans to hike parking charges in the city centre are on hold and a raft of events, vouchers and discounts are planned to lure back nervy shoppers. Council chief executive Sir Howard Bernstein has asked companies to give their staff an hour off work and Vaughan Allen, boss of the city centre management quango Cityco, is urging local businesses to support “the drive to get people back into the shops, bars and restaurants”.

Rescuing the ‘Manchester brand’ of the city centre as an enticing location to shop, relax and invest in is the driving force of the campaign, with Marketing Manchester’s director of strategic marketing Rachel Combie explaining to the business newspaper Insider how “the trouble isn’t what this city is about and isn’t what we want to be known for”. Recognising the potential damage off-message youths rioting in the streets may do to the brand, with an initial 20 per cent drop in visitors to the centre the Saturday after the disturbances, Leese told businesses he needed their help in “getting the message out that Manchester is open for business as usual”.

Unemployment in the North West rose 13 per cent in the last three months, and Leese defends the business-focused recovery on the grounds that “the coming weeks will be a difficult time for city centre business – a major source of employment for Manchester people”. However, any hopes Manchester’s leaders may have in healing the city by feeding the commercial interests of its centre are misplaced. For the success of Manchester’s brand in attracting private investors and wealthy consumers rests on the stagnant wages and widespread unemployment necessary for its cheap service economy.

Cheap labour

On the face of it the city’s leadership would appear to have had some success in managing the local impacts of the transition from mass industry to a retail and ‘knowledge’ economy based on workers in high tech industry, business services, media and IT, plus the shop workers, call centre workers, cleaners and security guards who serve them. While 221,000 manufacturing positions were destroyed between 1981 and 2006, as technological advances enabled industrial companies to dispense with the need for a mass workforce and relocate their remaining shop floors to countries with more easily exploitable staff, the number of jobs in the city region overall rose by 11.3 per cent, of which the majority were in the rising service sectors according to the Manchester Independent Economic Review (MIER).

Closer inspection of the changing nature of both the workforce and work reveals deep and growing inequalities. Segregation between the relatively wealthy areas south of the city centre, with its universities, airport and the regional industrial hub of Trafford Park, and the manufacturing-dependent inner cities and former mill towns to the north grew enormously. Between 2003 and 2008, before the recession, the south gained 24,600 private sector jobs. The north lost 2,700. The decline was only partly masked by Labour’s expansion of the public sector workforce, itself set to be dismantled under the Coalition’s austerity measures.

The private workforce that has developed is on the whole characterised by a polarisation between relatively secure and high paying jobs and a bulk of insecure, de-unionised, low paid work. Many of the fastest rising employment sectors were in the celebrated knowledge economy, with financial and business service occupations rising by 120 per cent in 25 years. This rise rests on what the Commission for the New Economy calls a “low skilled equilibrium where businesses can compete successfully on low cost, low skill business models”. In other words, cheap and disposable labour. Such jobs have high turnover, with the Manchester Monitor noting a replacement rate of around 14.2 per cent each year.

The reality behind the brand

Manchester’s increasingly centralised political and business elites have played their role in this by joining hands in a drive to attract private investment and rejuvenate the city’s real estate core. Marketing Manchester is but one of a ‘Manchester family’ of various advertising, consultancy and lobbying agencies designed to promote the city’s brand to the highest bidder. Vast regeneration schemes have been put into action over the last decade with the stated intention of improving the social housing and living standards of the city’s working class.

According to MIER the actual impact of the projects was to clear the way for a vibrant ‘city living’ housing market, finding that the impact on inner-city Hulme’s £400 million regeneration was to create “a growing trend for local families to be priced out of the owner occupation market by higher earning professionals and childless households, displacing families to more affordable areas”. The much-vaunted redevelopment of East Manchester created just 3,000 jobs in 10 years – woefully undershooting its target of 10,000.

This style of ‘regeneration’ and the reliance of Manchester’s moderately successful knowledge economy on cheap labour makes it no accident that the glitz and prosperity of the city centre is nestled among inner city estates with the highest rate of severe child poverty in Britain, the lowest life expectancy in England and a youth unemployment rate that has consistently languished at 30 per cent for the last 20 years. Manchester is the most unequal city in the UK, according to the Centre for Cities. This is not despite the social engineering and reforms of past decades, but because of it. This is the reality of the Manchester brand.

There are alternatives

Last April mothers campaigning to save their Sure Start centres questioned Richard Leese on why his city was spending money on subsidising leisure and tourist interests when their own public services were being cut and outsourced. His answer was that the era of globalisation makes it a necessity for Manchester to attract business growth if it is to provide jobs, both through providing good “quality of life” for the employees of incoming businesses such as the Bank of New York Mellon and for facilitating the city’s burgeoning tourist and conference industry, worth £2.7 billion to Manchester alone in 2009.

In so far as globalisation is a force necessitating the staggering inequalities of both Manchester and Britain however, with the free movement of capital that supposedly enables it to up sticks and leave if politicians do not cater to its interests, he is wrong. For all their issues, the relative egalitarianism of the social democratic welfare states of Scandinavia has not been gravely undermined despite their own service economies being even more open to trade than the UK’s. A ‘knowledge economy’ does not have to be inequitable.

In reality, the roots of our social tensions are as much political as they are economic. The dirty secret of the free market is that the knowledge economy is not particularly profitable for private enterprise, as it requires long term and risky investment in research and development that can be easily stolen by rivals. Service workplaces such as call centres are notoriously difficult to unionise, but since the 1980’s businesses in the UK have also relied on the nanny state to impose draconian anti-union legislation to lower their labour costs.

Land and property

The state has also frequently stepped in to socialise the risk of costly investment while allowing profits to be kept in private hands, be it through the government subsidising high speed rail, advanced technology research in the arms industry, or a local authority signing off a PFI contract. In 2005 every pound in private venture capital start-up finance in the North West was matched by eight pounds from public bodies such as the North West Development Agency. Even then, British companies are still sitting on £600 billion in reserves – roughly a quarter of GDP – for want of lucrative investment opportunities with which to plough their cash back into the economy.

In the UK, the solution to this problem was the encouragement of a long credit boom between 1992 and 2007, whereby the consumption businesses rely on for their sales was sustained through the ability of households to refinance their mortgages in a buoyant housing market. Manchester’s own political and business class surfed this wave, focusing their efforts on building an attractive brand and revitalising the city’s assets for the service economy and its attendant new middle class.

Careless amounts of taxpayers’ money have been flung at this, with the council overpaying Marketing Manchester £421,000 last year and not bothering to claim it back. The justification is that the city sees “a return on investment of £32.10 per £1 of subvention provided”, but this investment does not appear to have been returned to the city’s strained public services. In the campaign to rebrand the riots proceeds from the sales of the “I Love MCR” mugs and t-shirts are to go to two local charities, Forever Manchester and Reclaim, but this one-off influx of funds may be of little comfort considering the council’s children’s services department slashed its spending on charities by 29 per cent in this year’s budget.

Special interests

In any case, hoping Manchester will be able to muddle through to the benefit of its residents based on the same mixture of attracting private investment and regional consumers is a lost cause. The credit-fueled consumption boom Britain has relied on is dead, even if the spectre of a global economy staggering from one crisis to the next is ignored. The wave has broken on the rocks. The PR campaign to return consumers to the city centre may have as much effect as former President George W. Bush urging Americans to shop in the aftermath of 9/11. Nevertheless, further dangers lie in the way the shocking images and bitter memories of the riots have been co-opted, rebranded and resold.

The weeks since the riots has seen no end of denial that the participants were, as lead councillor for the city centre Pat Karney put it, “fit to be called Mancunians”. Chief Executive of Greater Manchester Chamber of Commerce Clive Memmot echoed this disavowal when he condemned the “violent, thuggish, selfish behaviour which affects our businesses, our community and our individual citizens.” But keep in mind how ‘community’ is a slippery word, particularly when leaders invoke it in urging us to pull together for a common cause.

For what is starkly apparent is that the ‘community interests’ served by bringing us flocking back to the city centre is not that of the community as a whole, but largely those elements who are enriched the most. And in conflating the communities of Manchester and its reputation with its retail hubs, bohemian nightlife and gentrified Northern Quarter, the other side to the city – decrepit housing in Miles Platting, closed youth centres in Moss Side and morning queues outside underfunded law centres in Longsight and Crumpsall – is concealed.

The reality of Manchester is that the poverty from which many of the rioters were drawn is not that of the deprived, the socially excluded, or as some would have it the morally or mentally deficient. It is the necessary consequence of Manchester’s method of wealth creation and the brand image that furthers it. No matter how much we protest our love for our city, if the hidden tensions produced by the sale of this brand continue to be ignored then it is inevitable our attention will only be regained by the wail of sirens, the stench of fire and the sound of shattered glass.

Richard Goulding

More: Features, Manchester

Comments

-

[…] Update: Looks like I’m not the only one who isn’t too keen on the I Heart MCR campaign. Richard Goulding over at Manchester Mule has written an article on the campaign, Marketing Manchester, and social issues in Manchester: I heart Coportate MCR. […]

Pingback by I heart MCR. — mightaswell. on August 26, 2011 at 1:01 pm -

I think this article sums up the real problems with Manchester. How does Bernstein find time to do things in Manchester when he is Chair of ReBlackpool and a director of Olympic Delivery Authority. Whilst Leese is also involved in a number of boards including Manchester Airport Group.

Comment by Patrick Sudlow on August 27, 2011 at 1:13 pm -

This is an excellent piece.

Just to add: ‘I love Mcr’ is a copy of the very popular ‘I love NY’ logo created in 1977 as a marketing tool to attract tourists put off by New York’s reputation at the time for violence and crime. It aims to bring visitors back to the city centre to spend money.

As with New York in 1977, it is a class response. Both campaigns come from business friendly city councils in order to protect the profits made by owners of ever more exclusive city centre shops and offices. They do nothing for the majority of people in an ever more unequal cities

The riots were predicted. ‘I love Mcr’ does nothing to stop them happening again.

Comment by Geoff Brown on August 27, 2011 at 3:15 pm -

The Pink pound has stolen Pride, the Croporate pound shapes our City centre and the Bankers’ pound brought us £110 million of cuts.

A clear analysis of the material base that underpins the Manchester riot. Without a change of political leadership and values the next ‘riot’ is set to be as big as the theft of the hopes and aspirations of a generation of youth abandoned by the City ‘leaders.’

A must read for all ‘real Mancunians.’

Comment by Mark Krantz on August 27, 2011 at 6:10 pm -

[…] This article first appeared on the Manchester Mule and is cross-posted here following a suggestion by AllyF. If you have a subject you would like to […]

Pingback by Rebranding the Manchester riots | Richard Goulding | RiotsLondon.info on August 31, 2011 at 11:09 am -

“contentious plans to hike parking charges in the city centre are on hold” – prices around the northern quarter (thomas street, dale street, port street, tariff street etc) have risen to an astonishing £2.70 per hour. I think this puts people off visiting Manchester more than the riots ever could

Comment by garry on August 31, 2011 at 12:38 pm -

[…] I heart corporate MCR […]

Pingback by Before the riots become utterly yesterday’s news - In Defence of Youth Work on September 4, 2011 at 8:12 pm -

fantastic piece Richard keep up the real facts behind this city the ones the council wont want reporting…..keep telling it like it is from ground level not from the rose tinted middle class perspective which the more affluent leaders will try and appease….

Comment by Joanne Harworth on September 5, 2011 at 5:21 pm -

Wha’s My Chemical Romance gotta do with anything? ‘Cos MCR is kinda already copyrighted to them…

Comment by Scott on November 4, 2011 at 11:17 pm

The comments are closed.